Scientists drill nearly 2 miles down to pull 1.2 million-year-old ice core from Antarctic

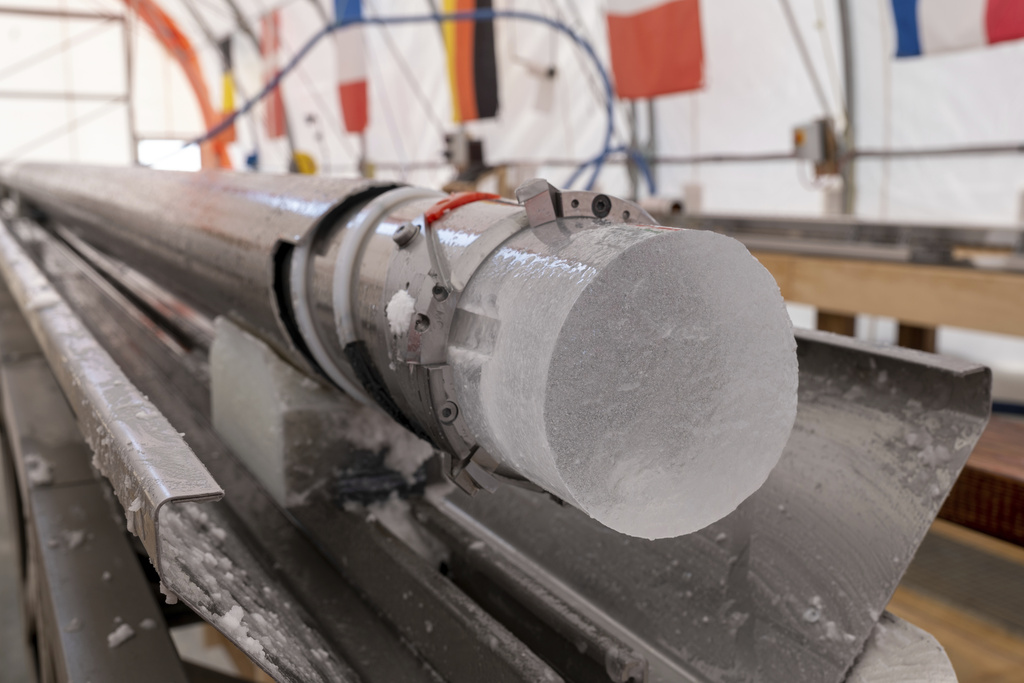

An international team of scientists announced Thursday that they have successfully extracted one of the oldest ice cores yet, drilling nearly two miles down to its final target - Antarctic bedrock, where the ice is predicted to be at least 1.2 million years old.

They said that variations in ice core data have evolved. This should provide insight into how Ice Age cycles have changed, and could help in understanding how atmospheric carbon changed climate.

"We'll have a better understanding of how greenhouse gases, chemicals, and dusts in the atmosphere have changed, thanks to the ice core project," said Carlo Barbante, an Italian scientist who studies ice and leads the Beyond EPICA project, which retrieved the core.

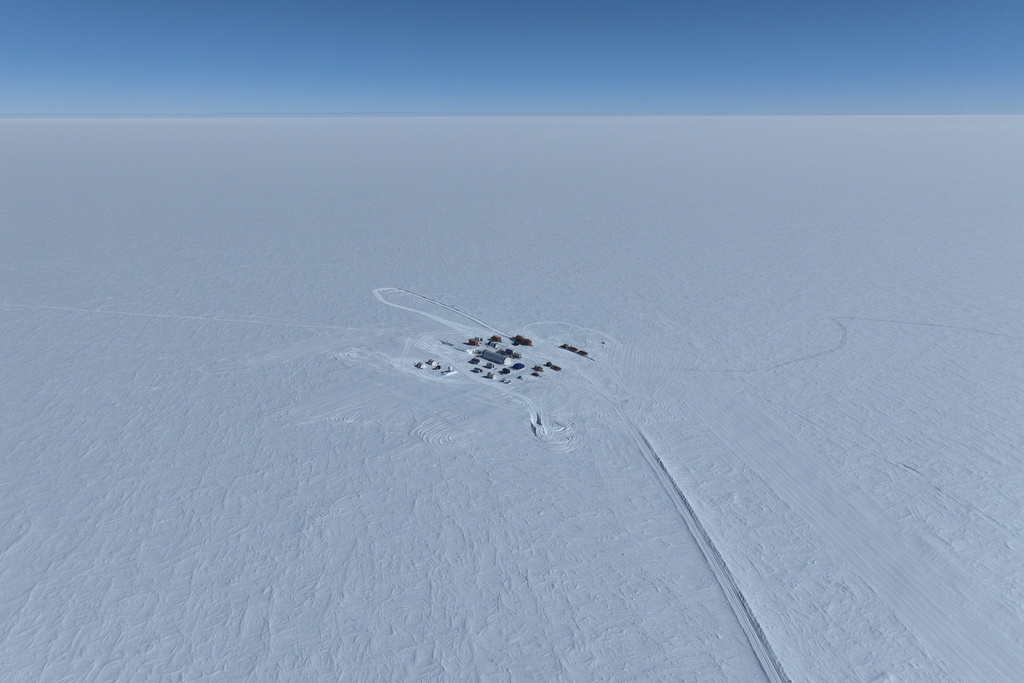

The same team had previously drilled a core that was around 800,000 years old. The new drilling went down to about 2.8 kilometers (approximately 1.7 miles), and it took a team of 16 scientists and support personnel, who worked each summer for about four years, drilling in temperatures that averaged around -35 degrees Celsius (-25.6 degrees Fahrenheit).

Italian researcher Federico Scoto was among the glaciologists and technicians who finished drilling at the start of January at a site known as Little Dome C, near the Concordia Research Station.

"We had a great moment for us when we hit bedrock," Scoto said. Isotope analysis indicated that the ice is at least 1.2 million years old, he said.

According to Barbante and Scoto, studies of an ice core from the Epica project revealed that levels of greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide and methane, during Earth's warmest periods over the past 800,000 years have not surpassed those of the time since the Industrial Revolution started.

"We're seeing today CO2 levels that are a full 50 percent higher than the highest levels we've recorded over the past 800,000 years," Barbante said.

The European Union supported the Beyond EPICA (European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica) project, backing it from nations across Europe, with Italy serving as the leading coordinator.

The announcement was quite thrilling to Richard Alley, a climate scientist at Penn State who was not connected to the project, and who recently earned the National Medal of Science in recognition of his work with ice sheets.

Alley stated that advancements in studying ice cores are significant because they help scientists gain a better understanding of past climate conditions and inform their knowledge on how human activities are impacting climate change today. He also noted that discovering the bedrock holds additional potential because researchers may uncover more information about Earth's history that's not directly linked to the ice core record itself.

“Honestly, it's truly amazing,” Alley said. “They will learn something truly wonderful.”

___

Associated Press reporter Melina Walling contributed from Chicago. Santalucia reported from Rome.

___

.

Post a Comment